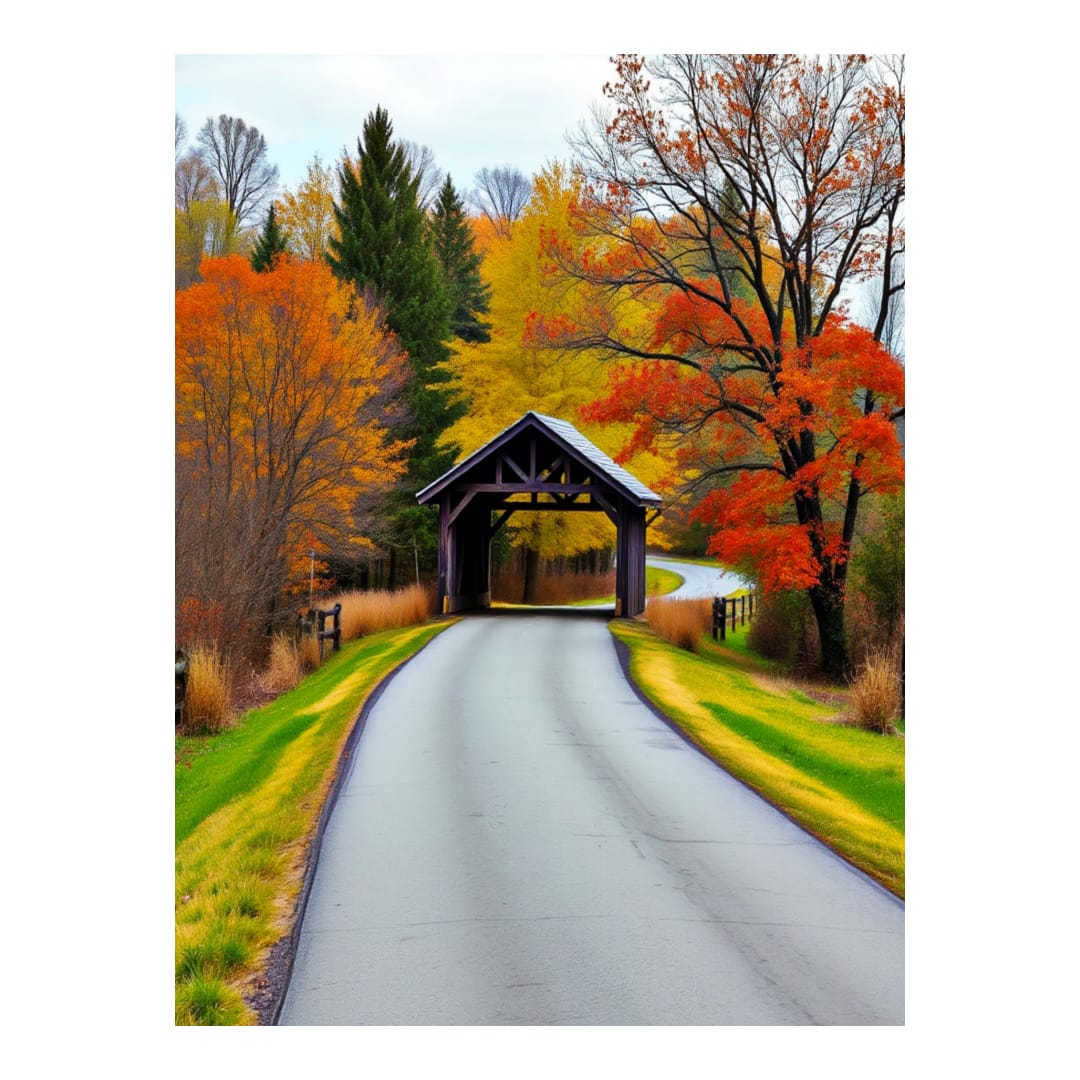

A parady of the movie, Bridges of Madison County

Under the Bridges

(The Parady)

When my father passed away in April, he left behind an apartment filled with a lifetime of accumulations, and, since I cared for him in his final days, the responsibility for sorting through and throwing away fell on my shoulders.

The clutter of the apartment was perplexing, and for the longest time, I could only stare, searching for a starting point. Finally, I rearranged the room into piles of throwaways, something somebody might want, and I’ll look at later. When I finished, the room was mostly a pile of trash. What took a lifetime to amass took the better part of a day to discard. Were these a man’s treasures reduced by death to trash.

Throughout the process, I looked for signs of him, signals about who he was, and the look at later represented the most potential to about who my father was.

I had grown weary as I slumped in the middle of the darkening room where I had stacked papers, letters, and a pouch filled with memorabilia. It included a wood- tipped bullet, a swastika armband, medals, dog tags, a gold-colored chain, which at one time held a pocket watch, fifteen silver dollars, and a few old pictures of my mother Rose, my sister Shawna, and myself. Some of the papers were official—service-related, a credit card PIN, and car insurance certificates dating back many years. An envelope contained a number of letters from a man named Richard Johnson and an announcement of my birth and his death. He must have been proud on that day. I had never met Richard Johnson, but heard Danny talk about him and knew I was his namesake.

Danny, my father, and Richard were lifelong friends. They grew up together, joined the Army, ended up in the same unit, and fought in Patton’s Fifth Infantry Division in Austria and Germany. There was a clipping from the Des Moines Register announcing his honorable separation from the service on the same date in 1947 and Father’s. How great it was to have a life-long friend like that .

They had stayed in touch all these years. The last postmarked letter was in 1969. As I read through the letters, I felt as though I knew Richard and that he was a lot like my father. But it was the last letter that I read, put down, and read again.

Dear Danny:

I’ve been told I have a degenerative heart condition, and the outlook is not good. The solution is a transplant, but I figure that’s not for me. I haven’t told Francesca and probably won’t just now. I have been carrying an awful secret, and I can’t think of anyone but you to share this awful burden.

It was the summer of 1965. I had taken the kids to the Fair for the week. Michael worked hard in 4H and was proud of an entry steer that won him first prize that year. I missed Francesca and had thought all week that I’d been working too hard and hadn’t paid proper attention to her lately. Through the week, my loneliness grew until, on Thursday, I announced to the kids we were going home a day early. In fact, it was my plan to drop the kids off at their grandparents so that when I surprised her, we could have the night to ourselves.

When I entered the lane, a cool breeze lifted from the meadow and whistled through the open window of my Chevy truck. I noticed an old pickup parked by the house, and at first, I thought it was Elmer’s, a local who leased some farm land from me, but as I pulled behind it, the Washington plates said otherwise.

When I approached the house, Jack didn’t greet me. You remember my Collie Jack. I sensed something was wrong when he didn’t rise to greet me but lay there on the porch, wagging his tail, but not lifting his head. As I walked to the back door, the cinder walkway crunched beneath my feet. The dark kitchen and flickering light inside caused me to pause at the back door and peer through the window. The flickering of candles drew dancing shadows on the walls, and as I focused, I could make out shadows dancing. The silhouette of two figures standing before each other and the glint of a wine glass between them left me breathless.

It was a long moment—the longest of my life. My life changed in those few moments, on the porch, in the twilight of an Iowa summer evening. In an instant, primitive urges swelled within me, rage and fear boiled and simmered into a sauce of sadness. As I peered through the window, I saw the images of my children, Michael and Carolyn.

Danny, better than anyone else, you know there was a time when rage and fear prepared us to kill, and like those nights when we half slept on frozen ground covered with straw in preparation to meet a faceless enemy, awaiting the sunrise and certain death for some, I could have been so moved again. But now there were the faces of my children and wife, and my life. In an instant, I was an old soldier. No longer ready for battle, wobbly-kneed and swimming in hopelessness. I returned to the Blazer, fumbled to start it, and without turning the headlights on, backed down the lane and left.

I never knew who that man was or who he was to Francesca. Maybe someone from her past. I don’t think so. It hurts to think he was just a drifter blown into this part of the world on a wind that swirled and shifted, and carried him to another place, and someone else. He took a lot with him, though, and left a lot too.

Life changed the minute I walked up the porch steps, on that summer evening in 1965. For a time after that, I wondered if Francesca might leave me, but she never did. She said I was a good man, and when I heard her say that, it hurt me and made me feel old. I was a good man, to be sure. But I also thought I knew what Francesca wanted and worked hard to provide it. I always thought she wanted security for herself and the kids, and we all pay a price for that. But I was always there for her. We were romantic together, but kids and security can sometimes dull that, and after that night, we were never close again. I often wondered if it was something I did or didn’t do. I know I desired a lifetime with her, not a moment. But then, we had so many memorable moments too.

Well, that night it rained, and I can’t remember a time when we had a summer that was any wetter. I couldn’t produce a crop that year, and interest rates and farm costs climbed in the years following. Farm life was never the same.

I remember days long ago, before the rains, and thank you for being my friend all those years. I wish you the very best.

Rich

Stapled to the letter was the notice of Richard’s death. He died of heart failure